Issue Briefs

Trump’s Vision & NATO’s Future: Streamline The Alliance For Modern War

Douglas Macgregor

July 19, 2018

It would be wrong for Europeans to conclude that President Trump wants to withdraw all US forces from Europe. The President simply wants the US military to be NATO’s security guarantor of last resort, not NATO’s “first responder.”

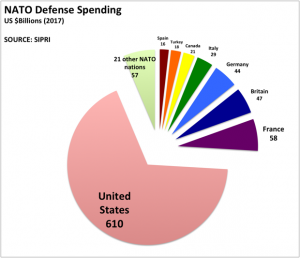

President Trump’s harsh words for Germany set the tone for a tense NATO summit — but America’s allies now know they have no right to assume the US will keep cutting fat checks to cover the cost of Europe’s defense. However, it would be wrong for Europeans to conclude that President Trump wants to withdraw all US forces from Europe. The President simply wants the US military to be NATO’s security guarantor of last resort, not NATO’s “first responder.”

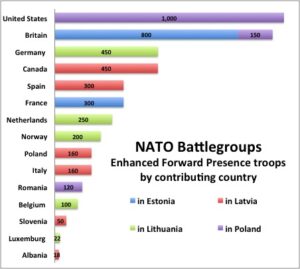

One reason is the character of the Russian threat. Instead of the massed motor rifle regiments of the Cold War, we’re now seeing disinformation and infiltration by Russian Special Operations Forces (little green men) on the pretext of aiding disaffected Russian minorities in countries like Estonia, Latvia, or Moldava. When Moscow thinks the time is ripe, it sends in the second wave: a rapid intervention by Russia’s standing, professional forces — primarily mobile armored formations ranging in size from 3,000-8,000 soldiers, tightly integrated with precision rocket artillery, surface-to-surface missile groups, and aerospace power. All of these forces are designed to operate under the cover of Western Russia’s formidable integrated air defenses (IADS) to keep NATO airpower at bay.

NATO’s preferred response is simultaneously too fragile and too sluggish. The first responders would be a spearhead of light forces, followed by a large U.S. military presence planted in Cold War-style garrisons, and ultimately the mobilization of European reserves. But Russian forces would not only rapidly crush the light infantryspearhead and achieve their strategic objectives long before the first European reservist shows up to fight: The Russians would also destroy US forces in their garrisons with precision strikes.

Extended nuclear deterrence is an even less appealing solution. Tossing nuclear pebbles at an opponent that will likely respond with nuclear boulders makes no sense. If it did, Great Britain and France would have committed their nuclear forces to NATO’s defense, but they have declined to do so. Unless Moscow takes the unlikely step of opening an offensive against Eastern Europe with nuclear strikes, any future Russian intervention must be defeated with conventional weapons, not intercontinental ballistic missiles(ICBMS) from the United States.

A second reason is not as widely understood: World War II and its sequel, the Cold War, are behind us, not in front of us. The age of mass mobilization-based armies has given way to limited, high-intensity conventional warfare — an era of integrated, “all arms-all effects” warfighting.

This new brand of “come- as-you-are” warfare requires highly trained professionals ready to fight effectively when the hostilities begin. The unified application of intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) systems, the whole range of cyber and electronic warfare capabilities, widely dispersed joint strike systems, and mobile, armored maneuver forces across service lines cannot be executed on the fly. To effect change in the way Europeans and Americans think about defense, the President must issue new marching orders to the Department of Defense:

- Turn US bases in Europe into austere Forward Operating Bases (FOBs) designed to receive deploying forces and then project them into training exercises or combat. Stop the expensive practice of building elaborate facilities for military communities in foreign countries, complete with family housing, schools, and grocery stores, that create jobs for foreign nationals, but do nothing for the U.S. economy.

- Establish permanent bases in the United States from which future forces will deploy and where service members’ families can live. End accompanied tours overseas except for the few specialists needed to sustain forces deploying through the FOBs.

- Build regionally focused, lean Joint Force Command (JFC) organizations to replace today’s overly large single-service headquarters. These bloated relics of World War II and the Cold War are too slow to deploy and they obstruct the rapid decision-making required in future warfare. Flatten command with the JFCs and exercise them regularly on short notice.

- Build self-contained Army formations of 5,000-6,000 soldiers for rapid deployment under joint command. Disband the large 15,000-18,000-man divisions. Extract billions in savings by shedding equipment and organizationsthat are no longer needed.

- Invest in new airlift and sea-lift to meet demands that commercial transport cannot. Invest in transportation support systems to off-load military cargo in unimproved locations.

NATO needs these reforms and European military leaders know it. But though these measures would save billions of dollars and dramatically improve the US armed forces’ readiness to fight, America’s senior military leaders will resist them. This, however, is a problem for President Trump, not NATO.

Gen. Curtis LeMay

History provides a model for how to fix this. When General Curtis LeMay took over Strategic Air Command, he discovered that SAC lacked the right operational focus and military capability; there were no detailed war plans, only broad directives. LeMay concluded there were not enough leaders with the elasticity of mind to meet the Cold War’s new demands for fast-paced exercises and deployments. LeMay found the ‘right people,’ he appointed them to command and staff positions, and SAC became the model of warfighting readiness. LeMay’s approach may be helpful to the President as he moves the Department of Defense and NATO in a new strategic direction.

|

Col. (ret) Douglas Macgregor is a Global Policy Institute Senior Adviser. He is a decorated combat veteran, the author of five books, a PhD and the executive VP of Burke-Macgregor Group LLC, a defense and foreign policy consulting firm in Reston, VA. Macgregor retired with the rank of Colonel in 2004. He holds an MA in comparative politics and a PhD in international relations from the University of Virginia.

The views and opinions expressed in this issue brief are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of GPI. |